Just after dawn on October 25, 1944, the Japanese sent the largest naval battle group ever assembled to destroy 130,000 American soldiers invading Leyte. Their goal was to destroy the American forces just moving inland, five days after the landings, to push them out of the Philippines. This battle and U.S. Navy Commander Ernest E. Evans’ heroic actions had a significant impact on hastening the conclusion of WWII.

Never before that day had one Sailor’s actions diverted the burden of attack from so many American service members so decisively as in the Battle off Samar. That man was Evans, a graduate of Muskogee High School and the U.S. Naval Academy.

“[Leyte Gulf], a key battle in the Pacific War, was almost a disaster for the United States,” said Samuel Cox, retired rear admiral and director of the Naval History and Heritage Command, in an April 2021 article from “The Oklahoman.” “If it hadn’t been for what Ernest Evans did, the battle would have gone much worse.”

The Japanese forces attempting to surprise the overmatched Taffy 3 task force were aggressively introduced to the unwavering courage and self-sacrifice of the U.S Navy’s finest. Three American destroyers, commonly referred to as “tin cans,” because they lacked armor, began the fight for their lives against a far superior force.

Among the attacking fleet, the Japanese super battleship Yamato, the largest battleship ever built with 18-inch rifles, outweighed the entire American defending force. It was a formidable part of a massive force consisting of four battleships, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 11 destroyers.

At the helm of the Fletcher-class destroyer USS Johnston, Evans assured himself a place in U.S. Naval history with his courageous initiative in the face of the overwhelming enemy. Before the order to attack was issued, the determined warrior began a lone preemptive retaliatory strike with extreme prejudice.

Evans entered Navy lore forever by laying a smoke screen to protect his fellow ships and navigating his vessel fearlessly into harm’s way to deploy his torpedoes.

The Johnston delivered the immediate first blow, instilling chaos within the Japanese naval ranks. Its 10 torpedoes tore the bow off the Japanese cruiser Kumano in the first few minutes of the three-hour battle. Here was the aggressive Japanese fleet, far outgunning and outnumbering its prey, being attacked and bloodied by the first ship it encountered.

Evans and his only 2,000-ton destroyer were much earlier announced to be the Navy’s readiest-for-battle warship. Evans let his assembled crew know his intentions as he took command at the USS Johnston’s commissioning in October 1943. “This is going to be a fighting ship,” he said. “I intend to go in harm’s way, and anyone who doesn’t want to go along had better get off right now. I will never retreat from an enemy force.”

Evans’s tactical blitzkrieg was everything a ship that size could accomplish in that short a time. But his audacious and successful counterattack against overwhelming forces off Samar was not enough for the brave Oklahoman.

The Johnston rejoined the frigate line of destroyers as they made their torpedo runs at the far superior forces. This action meant the small Taffy 3 task force presented a “larger than real” profile in the water to Japanese Admiral Takeo Kurita on his flagship Yamato. By now in the battle, more than a hundred pilots from the Jeep carriers and land bases nearby were swarming the Japanese fleet.

Although his ship had already fired all its torpedoes, Evans wanted to protect his fellow sailors as much as possible with his ship’s five 5-inch guns. The well-trained crew fired more than 800 rounds in the battle.

By drawing fire away from the Jeep carriers he was protecting, his ship was taking hits from powerful 14-inch guns. Despite severe damage to his ship and his wounds from Japanese fire destroying the bridge, Evans repeatedly put the Johnston between the enemy and the more vulnerable U.S. ships. This saved the lives of thousands of his fellow sailors.

This second suicide run met with far less success against the enemy. After almost three hours of battle, the Johnston eased over on her side for 25 minutes until finally sinking.

Her early valiant effort meant the Johnston proved decisive. Without air cover, the enemy, confusing the aggression to be a genuine effort made by a more significant force, broke off the attack and headed for Japan.

Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz wrote afterwards that the success of Taffy 3 was “nothing short of special dispensation from the Lord Almighty.”

Evans earned the respect of all Navy personnel forever for his courageous actions, but he lost his life at 36 that day, along with 185 members of his crew. His body was never recovered when the USS Johnston sank after fighting valiantly for three hours.

Evans was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor and a Purple Heart Medal for sparking the decisive victory in Leyte Gulf. He also shared in the Presidential Unit Citation awarded to Taffy 3 for this action.

On Sept. 28, 1945, shortly after World War II concluded, Evans’ Medal of Honor was presented to his wife, Margaret, in San Pedro, California. The ceremony was attended by his mother, sister, and sons Jerry and Ernest Jr.

Evans is one of only two destroyer captains from World War II to receive the Medal of Honor.

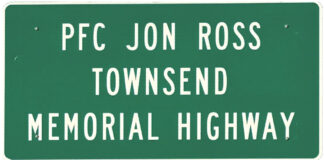

Evans’ exploits have now been interwoven into the Navy’s legacy, as his name has graced one decommissioned warship and a building at the U.S. Naval Academy. Last year, the Navy announced that the USS Ernest E. Evans, a DDG 51 Flight III Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer, will soon be the second warship named in his honor.

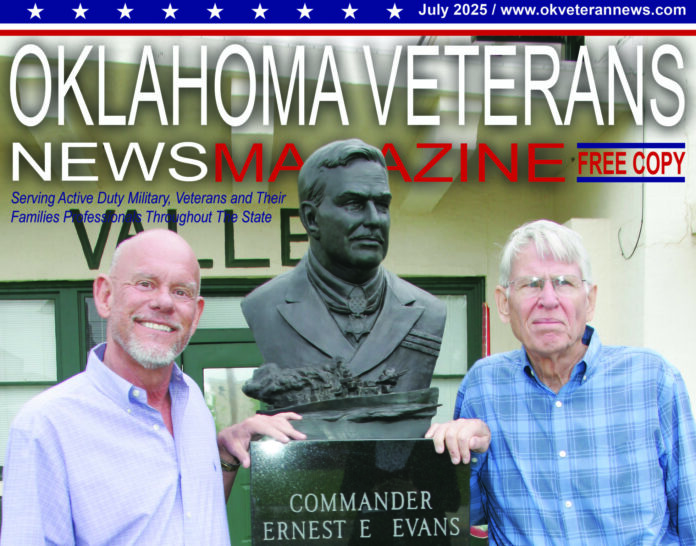

On May 7, Oklahomans demonstrated that their servicemen and women are never forgotten during a solemn ceremony to unveil a bronze bust of Evans. In front of the Three Rivers Museum, a monument was dedicated to Oklahoma’s most celebrated World War II Navy hero in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Retired U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Stephen Reagan, who resides in Norman, and his wife, Alice, spearheaded the effort to honor Evans. The campaign to raise funds and acquire the resources to create the monument took almost four years.

“I consider my work to help Muskogee honor Commander Ernest Evans one of the most significant things I have ever done,” Reagan said. “It’s a good feeling to help others. I am very proud to have Alice present, who helped make it a great day for me.”

Nationally acclaimed artist Paul Moore from Norman created a bronze bust of Evans wearing his Navy Medal of Honor. An identical bust, a gift from Reagan and his donors, is displayed at the US Naval Academy Museum.

The bust sits atop a tall square black granite pedestal. Below his image at the front of the bust is a miniature model of the USS Johnston in bronze, firing her five-inch guns and creating a smoke screen.

Patrick Cale, the Mayor of Muskogee and owner of Muskogee Marble & Granite, was the only corporate donor to the project. He provided the pedestal that features Evans’ significant career dates on the front, while the back showcases his Medal of Honor citation.

Reagan and his wife, Alice, volunteer five mornings a week with the Dale K. Graham Veterans Foundation in Norman. It is accredited as a Regional Veterans Service Organization. Its dedicated staff members work tirelessly to help all service veterans and their families receive their full military service benefits. story/photo by Darl Devault, contributing editor