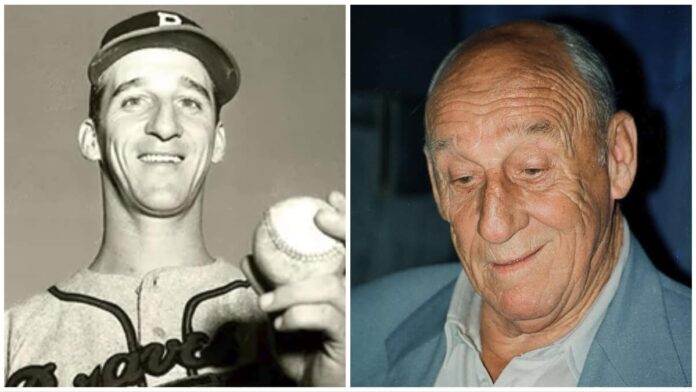

National Baseball Hall of Fame pitcher Warren Edward Spahn accomplished something few Major League Baseball pitchers have—he led the major leagues in wins for the years spanning his lengthy career. What makes this even more remarkable is Spahn’s major-league career was interrupted for three and a half years while he distinguished himself as a U.S. Army combat engineer in Europe in World War II.

“People say that my absence from the big leagues in World War II may have cost me a chance to win 400 games,” Spahn said in an interview in 1998. “But I don’t know about that. I matured a lot in those years in the Army. I believe I was better equipped to handle major league hitters at 25 than I was at 22. Also, I pitched until I was 44. Perhaps I wouldn’t have been able to do that otherwise.”

He had a stellar career after switching from first base to pitching at a high school in Buffalo, New York. Propelled by his almost unhittable fastball, his team won the local high school championship in his junior and senior years. He attracted the attention of scouts by throwing a no-hitter as a senior. He signed with the Boston Braves in 1940 before graduation.

The rookie reported to the Braves’ Class D club and had a good year. His teammates nicknamed him “Spahnie.”

He worked his way up through Class D, C, and B-ball, growing and throwing stronger every year. After a season in A ball in Hartford, Conn., his 17 wins and less than 2.0 earned run average (ERA) warranted a call-up to the Braves. He arrived at the end of the 1942 season at six foot and 175 pounds. He pitched 15 innings as a major leaguer and notched seven strikeouts.

By 1942, World War II was increasingly depleting major-league rosters, and Spahn was a healthy 21-year-old. After the season ended, he joined the Army from his home in Buffalo. After basic training, he was sent to Oklahoma, where he met his future bride, LoRene Southard.

He trained as an Army combat engineer at Camp Gruber, near Muskogee, for seven months in 1944. Camp Gruber was started after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and its 2,250 buildings were finished in four months. Thousands of soldiers trained at Camp Gruber during World War II, and its extensive facilities included a 1,600-bed hospital.

In the summer of 1944, he was shipped to Europe. Already promoted to staff sergeant, his leadership ability was apparent. Upon arrival in Belgium, Spahn’s 276th Engineer Combat Battalion was soon helping the First Army push back the bulge in what came to be called the Battle of the Bulge.

Spahn’s engineers were put to work clearing roads of the wreckage of German Tiger tanks and other vehicles. The troops were assigned to guard vital bridges and clear roads of snow and mines. They also cleared airstrips and constructed gun and radar pits for anti-aircraft artillery.

On Jan. 26, 1945, the battalion constructed its first bridge under fire. Five days later, the first combat casualty was suffered in a mine explosion when an engineer engaged in destroying mines was killed. The unit earned its first battle star for The Battle of the Ardennes.

After crossing the Roer River, the engineers were put to work maintaining the roads used to approach the Rhine River. They supported infantry by building footbridges across rivers.

Three months later, in Germany, Spahn’s unit helped repair the only remaining bridge spanning the Rhine River, the vital Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen. Although they had heavily damaged it, the Germans had failed to destroy the bridge with explosives when they withdrew across the Rhine.

Determined to use the river as a natural barrier to the Allies’ advance, the Germans attempted daily to destroy it with artillery and bombs, but their efforts were unsuccessful.

Repairing the initial demolition damage and the daily damage to the old railway bridge was extremely dangerous for the combat engineers. They were also vulnerable when a layer of roadway was added over the railroad tracks. This maintenance assignment proved to be the most dangerous one in the European theater of operations during the war.

Casualties were heavy as the engineers of the 276th worked to repair the bridge and provide a second lane for two-way traffic. Spahn earned a Purple Heart for what he says was only a scratch on his foot when he was caught on the bridge during a bombing attack.

Although it allowed the Allies to pour five divisions of troops into the first foothold east of the Rhine for 10 days, the bridge had taken a beating. On March 17, 1945, while 200 men from the battalion were working on the bridge, it collapsed due to structural damage and overload. Many Americans were killed, including 22 engineers from the 276th.

Readers can watch a video wherein Spahn recounts the last hour before the bride fell: Warren Spahn, Former MLB Pitcher, Shares His Remagen Bridge Experiences

The 276th received a Presidential Unit Citation for their maintenance efforts on the bridge. The unit also received its second battle star for participating in the Battle of the Rhineland.

In recognition of his leadership under fire, Spahn received a battlefield commission to second lieutenant. He finished his combat career helping his unit earn its final battle star in the push deep into Germany in the Battle of Central Germany.

Accepting his promotion to officer required him to stay in the Army nearly a year after the war’s end. Spahn was first transferred to the Army of the Occupation. The 276th was disbanded to provide reinforcements for the Pacific and was deactivated.

His battlefield promotion was one of the few for a major leaguer during the war. “I did not know it at the time, but that promotion cost me dearly when the war was over,” Spahn said. While other major leaguers were home from the war and playing again, Spahn built hospitals in Nuremberg, West Germany, with the Corps of Engineers.

Finally returning to pitch for the Boston Braves, Spahn married LoRene and eventually made Hartshorne, Oklahoma, their home. He went on to become the winningest left-handed pitcher ever in the majors. “Every pitch had a thought behind it,” Spahn said. “I am well remembered for saying, ‘Hitting is timing. Pitching is upsetting timing’.”

As a 17-time All-Star with 363 wins and the 1957 Cy Young Award winner in 21 seasons in 1965, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973. At 44, he transitioned into coaching and management, retiring from baseball in 1982.

He was honored in 1999 with the creation of a namesake award to celebrate the winningest left-handed pitcher in the majors each year. Every year, the best lefty in the majors traveled to Guthrie, Oklahoma, where they received the Warren Spahn Award trophy.

Spahn died in November 2003, at 82, a few months after attending the unveiling of a nine-foot bronze statue sculpted by Oklahoman Shan Gray at the Atlanta Braves’ Turner Field. Readers can find an identical statue outside the Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark in Downtown Oklahoma City. Story and photos by Darl DeVault, contributing editor