Cannon Roar, Infantry Charge

Boom! Boom! The ground shook as Union and Confederate howitzers volleyed across the battlefield. Smoke rose while 2,000 spectators filmed or covered their ears. Children cried. The Reenactment of the Engagement at Honey Springs, July 17, 1863, had begun.

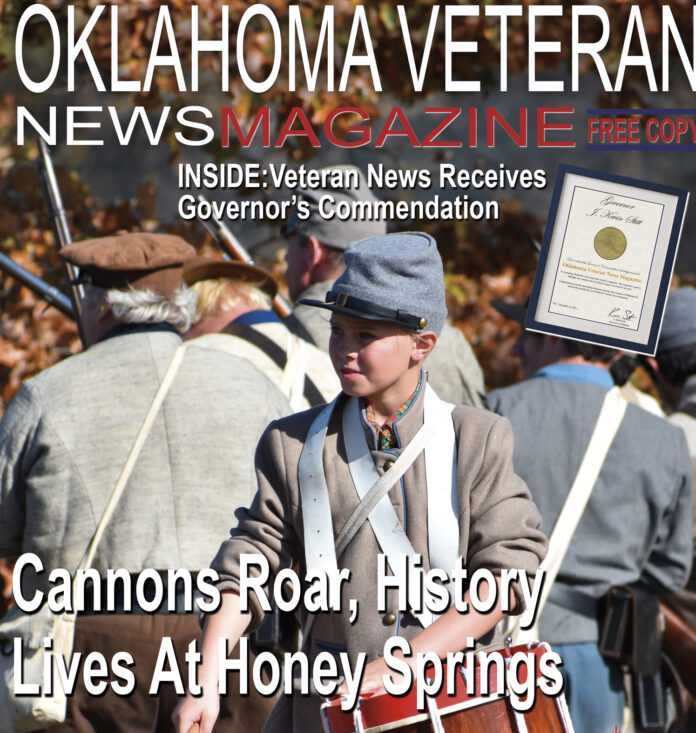

Six Confederate cannon fired in sequence. Four Union cannon answered. Amidst the smoke, Confederate cavalry flanked left, sabers in hand, while rebel infantry in grey wool uniforms emerged from the woods. At the midpoint of the battle, they spread into two, 20-man lines and advanced toward the Yankee line, believing they were retreating.

“Yee-haw! Yip-Yip!” Johnny Reb yelled, firing at two infantry squares of 25 Union soldiers standing about 50 feet apart. Two men in blue fell. But Billy Yank held firm and in the actual battle, fired back – just as reenactors did on November 7 and 8. In disciplined turns, the Union squares fired volleys at the rebel line 150 feet ahead. The left column fired – three men in grey dropped. The right column fired – two more grey men fell.

Then, Northern Army cannon thundered, covering the Yankees’ advance. The Graybacks retreated across Elk Creek. A narrator explained each step of the battle, which took place on part of the actual battlefield, for onlookers.

Diverse participants

Historical Society information says the combatants in 1863 came from the 1st Division, Army of the Frontier (USA), commanded by Maj. Gen. James Blunt and the Confederate Indian Brigade led by Brig. Gen. Douglas Cooper. They included “American Indians, veteran Texas regiments, and the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment (the first African American Regiment to see combat in the entire Civil War)…Cooper reported his losses as 134 killed and wounded, with 47 taken prisoner. Blunt reported his losses as 17 killed and 60 wounded.”

Outcome

The Union victory ensured federal control of Fort Gibson in Indian Territory and Fort Smith in Arkansas. However, American Indians in Indian Territory were devastated. The Historical Society estimates between 11-24 percent of tribal members died and after the war, tribes were forced to sign treaties with the U.S. government that made them give up or sell much of their land.

Rest and Relaxation

After the reenacted battle, blue and grey cavalry soldiers allowed children to pet their horses. Attendees and reenactors lined up at food trucks, although it was startling to see Union and Confederate soldiers eating hot dogs and tacos together.

Nearby, Sutler Row businesses sold books, wooden guns, games, and reproductions of 19th Century household items. Demonstrations included laundresses, a piper, and sanitation methods. Union and Confederate camps housed reenactors and their families over the weekend, adding authenticity to the event.

Molly Hutchins, Site Director, estimated 2,500 school children attended Education Day, Nov. 6, and 5,000 came for the two reenactments. She said 300 reenactors from 10 states participated.

Educating Visitors

Trait Thompson, Executive Director of the Oklahoma Historical Society, explained the purpose of the reenactment is “to give our visitors a better understanding of the Civil War in the Indian Territory.” Asked what he hopes people take away from attending, he replied, “Understanding a little bit more about the people that fought here, the reasons they fought and how the battle may have looked. It’s always good when you can match fun and education together.”

Reenactors Voices

For many participants, reenacting is a passion. “I love history. That’s why I do this,” said Sean Mize of Edmond, a Confederate cannoneer. Union soldier Preston Ulrich of Moberly, Missouri, has been reenacting since age 13. Now 17, he participates 6 to 8 times a year with his father. “I think it’s fun. It’s a good way to escape modern life. It lets us dip into what our ancestors did.” For Colleen Jefferson of Ft. Worth, “I think this conflict is the defining conflict for the nation because it challenges our beliefs about our founding principles.” Jefferson has been reenacting for 14 years.

About the Battlefield

Oklahoma’s Historical Society owns and manages the 1,100 acres of the Honey Springs Battlefield east of U.S. Highway 69 between Oktaha and Rentiesville, Oklahoma. It was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 2013. The Society hosts and schedules the reenactment every two years. Planning takes a full year, with support from organizations such as the Friends of Honey Springs Battlefield, a 501(c)(3).

Four monuments list the fighting units involved. Please visit the museum to understand the battle. It has a gift shop and two main rooms. One room offers recorded messages on telephones from dairies and papers of participants and mannequins in period uniforms and weapons. The second displays maps of the engagement, explanations and a replica supply wagon. A few artifacts recovered from the battlefield like minie bullets, lead and canister balls, and camp equipment, are on display.

On one telephone recording, the voice of Col. James Williams, Commander of the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry recounted events. “…I moved my regiment… loaded and bayonets fixed under sharp fire, to within 40 paces of the rebel line, without firing a shot, then halted and poured into their ranks a well-directed volley of buck and ball…which sent them to grass…which they never recovered.”

Largest Civil War Battle in Indian Territory

Hutchins emphasized the site’s importance: “We’re the site of the largest Civil War battle fought in Indian Territory…We are also known as one of the most culturally diverse battles in the entire Civil War. Preservation of our site is important for those reasons. We are dedicated to sharing the history of the (battle) and honoring the men who fought here.” •

• Story by Retired Lt. Col. Richard Stephens, Jr., USAFER. See Rich Travel Niche

To learn more, visit https://www.okhistory.org/sites/honeysprings.